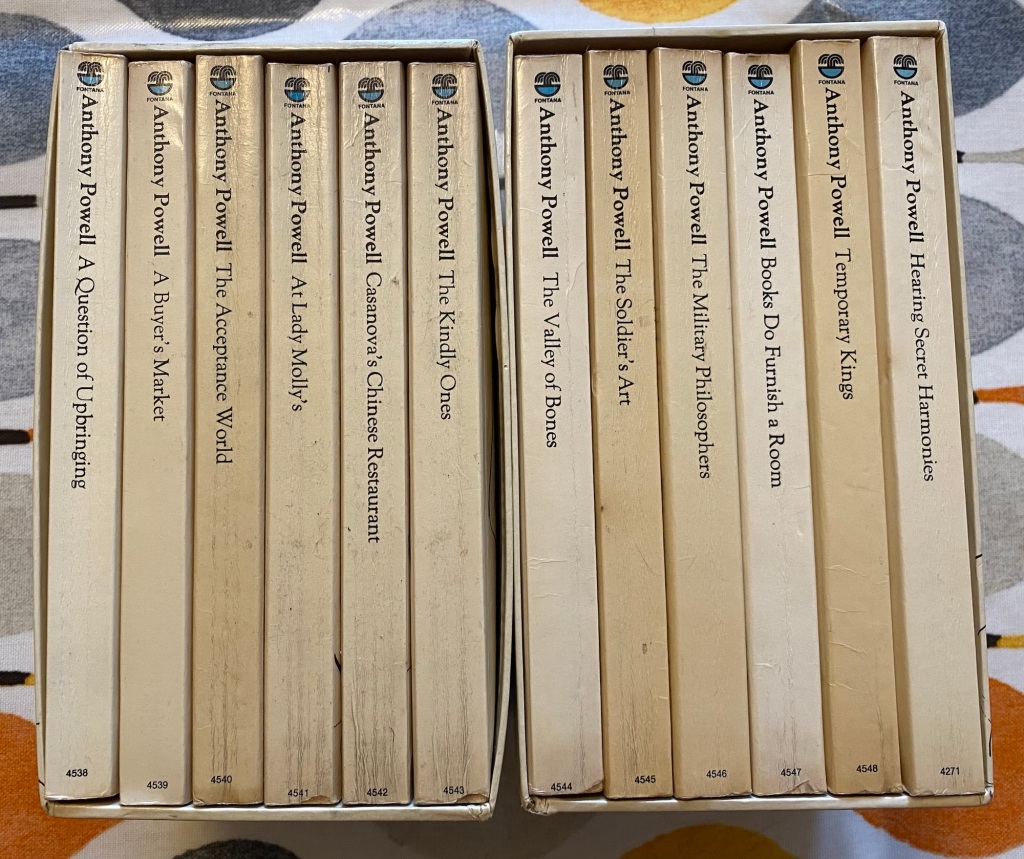

This is the fifth instalment in my 2024 resolution to read a book per month from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time sequence. Published between 1951 and 1975, and set from the early 1920s to the early 1970s, the sequence is narrated by Nicholas Jenkins, a man born into privilege and based on Powell himself.

The fifth volume, Casanova’s Chinese Restaurant, was published in 1960 and begins by considering a bombed-out pub from World War Two, which triggers memories of the past and events of the 1920s and 1930s. It expands on relationships from the previous novels and portrays various marriages.

This shifting back and forth through time means characters who have died are resurrected, and minor ones expanded upon. Although perhaps they would rather not be, finding themselves the subject of Powell’s razor-sharp observations:

“The sight of Mr Deacon always made me think of the Middle Ages because of his resemblance to a pilgrim, a mildly sinister pilgrim, with more than a streak of madness in him, but then in every epoch a proportion of pilgrims must have been sinister, some mad as well.”

“[St John Clarke’s] name was rarely seen except in alphabetical order among a score of nonentities signing the foot of some letter to the press.”

The gathering alongside Mr Deacon at the pub leads to two of the main characters in this volume: Moreland the composer whom Nick befriends, and his acquaintance, the really quite disturbing music critic Maclintick.

“Under his splenetic exterior Maclintick harboured all kind of violent, imperfectly integrated sentiments. Moreland, for example, impressed him, perhaps rightly, as a young man of matchless talent, ill equipped to face a materialistic world.”

Marriage is the major theme of this volume, and the scenes of Maclintick’s domestic life are truly horrible. Only marginally more disturbing are the descriptions of Nick’s schoolfriend Stringham battling with his alcoholism, and his childhood secretary Miss Weedon opportunistically using it to control him.

There are of course lighter sides to the tale too. Powell takes his satirical eye to relationships between the sexes, both in dating:

“Barnby always dismissed the idea of intelligence in a woman as no more than a characteristic to be endured.”

And later in marriage, as Moreland laments: “I shall be glad when this baby is born. Matilda has not been at all easy to deal with since it started. Of course, I know that is in the best possible tradition.”

Powell doesn’t dwell on Nick’s marriage to Isobel in great detail, but in the brief glimpses we have they seem happy together, despite sadnesses to contend with. Nick also seems to enjoy his extended, eccentric in-laws. Erridge has gone to fight in the Spanish Civil War, without success:

“His time in Spain seems to have been a total flop. He didn’t get up to the front and he never met Hemingway.”

There’s also Nick’s description of his mother-in-law Lady Warminster, more affectionate than biting: “She looked as usual like a very patrician Sibyl about to announce a calamitous disaster of which she had personally given due and disregarded warning.”

By far my favourite scene was at Lady Warminster’s party, where the reader gets to know St John Clarke further, his having made only brief appearances in previous volumes:

“He came hurriedly into the room, a hand held out in front of him as if to grasp the handle of a railway carriage door before the already moving train gathered speed and left the platform.

‘Lady Warminster, I am indeed ashamed of myself,’ he said in a high, rich, breathless, mincing voice, like that of an experienced actor trying to get the best out of a minor part in Restoration comedy. ‘I must crave the forgiveness of you and your guests.’

He gave a rapid glance round the room to discover whom he had been asked to meet, at the same time diffusing about him a considerable air of social discomfort.”

Nick’s touchstone of Widmerpool only makes brief appearances: “I should never have gone out of my way to seek him, knowing, as one does with certain people, that the rhythm of life would sooner or later be bound to bring us together again.” but he manages to seem an entirely menacing background presence regardless.

I’m enjoying A Dance to the Music of Time more and more. Powell’s satire is never bitter or leaves me feeling uncomfortable, as satire can sometimes do. He’s clear-sighted and affectionate without being sentimental. Returning to the sequence is starting to feel like catching up with your wisest, wittiest friend. An absolute delight.

“Marriage, partaking of such – and thousand more – dual antagonisms and participations, finally defies definition.”

To end, if either of The Proclaimers are married, then I hope they wore nicer suits at their actual weddings: